Twisted wing flies

The Strepsiptera are one of the strangest insect groups, little known to most people, and hardly seen even by entomologists unless they make a special effort to study them. All are obligate endoparasites in other insects and, as so often in parasitic groups, there are many unique morphological and biological adaptations.

Their relationship to other orders is still not clear; they have been variously placed within the Coleoptera (as the Stylopoidea), as sister-group to the Coleoptera, as sister-group to the Diptera, or even outside the endopterygotes altogether.

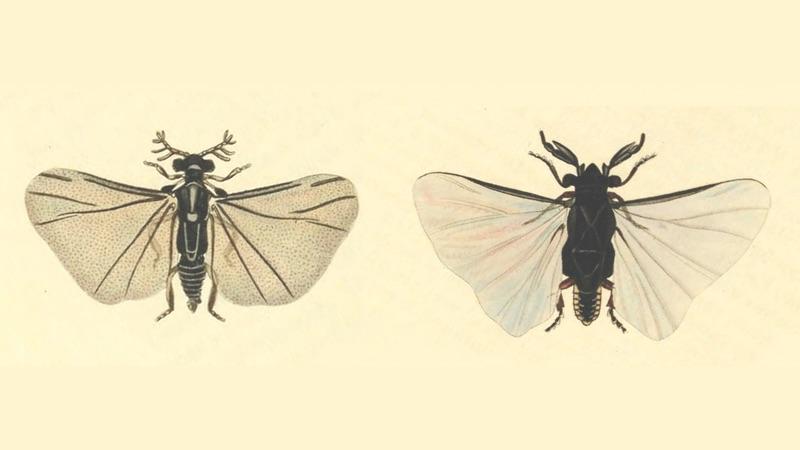

Illustrations of two male adults of Strepsiptera (from Curtis 1823)

Illustrations of two male adults of Strepsiptera (from Curtis 1823)Male Strepsiptera are perhaps the least modified stage of this group, but even they have many peculiar features. Like the Diptera they have only one pair of functional wings, but these are the hind wings, and it is the fore wings that are modified into long halteres, the reverse of the Dipteran situation. In museum specimens these halteres become contorted, which originally gave rise to the alternative common name of twisted-wing insects (though some recent texts attribute this name to a supposed twisting of the hind wings during flight). Males are rarely seen, as they do not feed nor live for more than a few hours but their image is familiar to many entomologists; early in its history the Royal Entomological Society adopted a figure of a male stylops as the emblem for its official seal, now also its logo.

In Britain the hosts of Strepsiptera are either aculeate Hymenoptera (particularly Andrena in the Apidae) or homopteran bugs. These ‘stylopised’ insects are often recognisable by unusual behaviour, such as becoming increasingly inactive as the parasites develop inside; a closer look will often reveal parasite heads protruding from the host abdomen.

Female Strepsiptera are endoparasitic, spending their entire life inside the host insect; they are neotenic with no legs or wings, and only rudimentary eyes, antennae and mouthparts. Her sclerotised head and thorax protrude from the host’s abdomen and she emits pheromones to attract males.

Stepsipteran parasites protuding from abdomen of Andrena similis Credit Robin Williams

Stepsipteran parasites protuding from abdomen of Andrena similis Credit Robin WilliamsMating occurs on the body of the host, the male inseminating the female through the brood canal which opens between her head and prothorax. The eggs hatch inside the female’s body into minute triungulin larvae; these emerge from the brood canal and rapidly disperse using their simple legs; they can sometimes be found on flower-heads. Once they have located a new host they burrow through its cuticle, moult into an apodous stage and then feed on its haemolymph. Pupation occurs inside the host’s body, with larval skins forming a puparium, as in some Diptera; the pupal head is visible outside the host. Males emerge and fly off in search of a mate, while females remain in the host, which is still alive even though much of its body may be occupied by the parasite.

Worldwide there are around 600 known species in 10 families; in Britain there are 10 species in 4 families.

Identification help