First published: 23 October 2025.

An Editorial published in Medical and Veterinary Entomology, “The migratory behaviour of salt marsh mosquitoes: Revisiting the evidence” asks whether long-distance movements by salt marsh mosquitoes should be considered migratory. And if so, what is the nature of this migration and why does it matter?

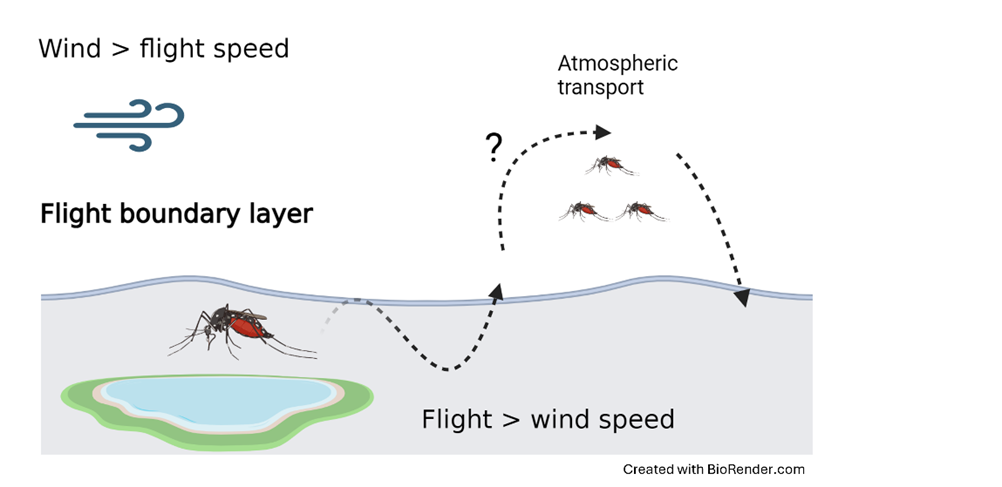

Many insects use the wind to transport themselves remarkable distances. This is part of a migratory response to seek favourable resources (e.g. better food or shelter) or to escape local pressures (e.g. predation or overcrowding).

It has been known for some time that mosquitoes are carried by the wind. Some species have even been caught on oil rigs over one hundred kilometres out to sea! Until recently, however, it was believed that these wind-borne flights were merely accidental.

Some salt marsh mosquitoes may utilise high altitude winds to migrate from breeding grounds.

Some salt marsh mosquitoes may utilise high altitude winds to migrate from breeding grounds.

Thanks to recent aerial sampling experiments our perspective on mosquito migration has changed. More mosquito species are captured at high altitude (>100 m above sea level) than previously thought and hitching a ride on the wind is most likely an evolutionary response to local conditions.

This shift in how we think about mosquito movement is important given that mosquitoes are a notorious biting nuisance and many species can transmit human and animal pathogens. While not all mosquitoes will undertake such journeys, the ability to utilise the wind for migration may expand the spread of pathogens beyond local habitats and borders.

Many historical reports describing long distance movement in mosquitoes involve species adapted to salt marsh habitat. Anyone who has visited coastal salt marshes knows that this ecosystem is constantly changing. Resident organisms must cope with the daily coming and going of the tides as well as the highly variable coastal weather. One mechanism of coping is to move away and find new grounds – in the case of mosquitoes, this could be to lay eggs or locate a blood meal. This is a risky strategy but under the right conditions, it just might pay off.

Co-author Dr Nadja Wipf sampling Aedes detritus on Dee Estuary, UK

Co-author Dr Nadja Wipf sampling Aedes detritus on Dee Estuary, UK

The Editorial begins with a reflection on an experiment in 1950s Florida, in which salt marsh mosquitoes (Aedes taeniorhynchus) – tagged with a radioactive compound – were caught up to 40 km (25 mi) away and over significant open bodies of water after just a few days following their release. Using this paper as a point of reference, the Editorial describes similar findings from other salt marsh species across the world and reconsiders salt marsh mosquito movement in the context of contemporary insect migration research.

Importantly, many of the salt marsh species described in the Editorial can transmit pathogens from animals to humans. Understanding their ecology and movement is therefore critical for determining the risks posed by emerging mosquito-borne viruses, especially in the context of a rapidly changing climate.

“This Editorial was born out of our departmental journal club and some reflections on research concerning salt marsh mosquitoes in the 1950s. On the Dee Estuary in the Northwest of the UK, we are conducting fieldwork to understand how these species cope with the pressures of a habitat that is constantly in flux. Migration is potentially one means of doing so but much more experimental work is needed to understand this fascinating behaviour and what it means for disease dynamics”.

– Chris Jones, Associate Editor, Medical and Veterinary Entomology

Want to be featured in our Journal Highlights?

Shine a spotlight on your research by submitting your papers to any of our seven journals for the chance to be mentioned on our news pages and social media